That is what some idiot over at the Washington post is saying: (H/T HotAir Headlines)

This Fourth of July, let’s celebrate courage. It took courage to split from England, courage to risk democracy and still more courage to dream up a constitution to preserve it.

Courage has been the signature virtue of almost every great American: Emily Dickinson was brave to warp grammar, Louis Armstrong was brave to blow jazz and Jackson Pollock was brave to paint splats.

Norman Rockwell is often championed as the great painter of American virtues. Yet the one virtue most nearly absent from his work is courage. He doesn’t challenge any of us, or himself, to think new thoughts or try new acts or look with fresh eyes. From the docile realism of his style to the received ideas of his subjects, Rockwell reliably keeps us right in the middle of our comfort zone.

That’s what made him one of the most important painters in U.S. history, and the most popular. He had almost preternatural social intuitions, along with brilliant skills as a visual salesman. Over his seven-decade career, that coupling let him figure out what middle-class white Americans most wanted to feel about themselves, then sell it back to them in paint. (He started working as an illustrator at 16, in 1910. He died, still in the saddle at 84, in 1978.)

You could say that Rockwell painted the backdrop against which American courage has had to play out.

A new show of 57 Rockwells, borrowed from the collections of Hollywood celebrities Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, opened Friday at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It includes oil paintings and drawings, and every one of them is a perfect depiction of what we’ve been taught to think of as true Rockwellian America.

There’s the small-town runaway, and the cop who takes him out for a malt before returning him home. Aw, shucks.

There are the three old biddies gossiping, imagined as so ancient and gnarled that Rockwell had to use a man in drag to model them. What a hoot!

There’s the remote blonde in her convertible being joshed by a couple of truckers. Jeez, lady, wontcha give those guys a wink?

In ads and magazine covers, on calendars and Green Stamps books — on any surface that took ink, for any client who could afford his fees — Rockwell sold us the vision of America as a place where troubles are never more than “scrapes” and flaws are always “foibles.”

Rockwell remains resolutely, immovably on the mild side even when he goes “serious,” as in his famous “Four Freedoms” series from 1942. (The conservative critic Dave Hickey, otherwise a Rockwell booster, has said that “when he’s doing ideas, he’s really awful.”) Rockwell’s vision of “Freedom of Speech,” included in the Smithsonian’s show, doesn’t invoke a communist printing his pamphlets or an atheist on a soapbox. It gives us a town hall meeting of almost interchangeable New Englanders, no doubt agreeing to disagree about something as divisive as the rates for those new parking meters. For this, the Founders risked powder and ball?

Of course, Rockwell’s true achievement wasn’t in his trepidatious, homogenized vision of the country. That existed already. (The Saturday Evening Post, for instance, for which Rockwell painted 323 covers, forbade him to depict blacks except in subservient roles. Toward the end of his career, Rockwell got Look magazine to publish a few heroic scenes from the civil rights movement — at just the moment when such subjects had moved into the mainstream of American thought.) Rockwell’s great accomplishment lay in selling us this tepid vision of ourselves as one we simply had to buy into, on a communal scale.

[…]

Rockwell’s greatest sin as an artist is simple: His is an art of unending cliché. The reason we so easily “recognize ourselves” in his paintings is because they reflect the standard image we already know. His stories resonate so strongly because they are the stories we’ve told ourselves a thousand times.

Those stories couldn’t have been otherwise. To sell the publications and goods his pictures were in aid of, Rockwell’s images needed to be grasped and digested in seconds — and, unlike really notable art, they reliably achieved such fast-food effects.

His young women are always “spunky” or “hotties.” Young girls are “impish” or “pure.” Husbands are “harried” and Grandpa is “kindly.” And young boys — as the art history scholar Eric Segal has pointed out — are either good and scrappy, busy roughhousing at the rural swimming hole, or urban and effeminate and overcivilized, in need of a good, toughening hazing.

Segal is part of a Rockwell reassessment that began around the time of the artist’s last Washington retrospective, held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art just 10 years ago. If the experts haven’t found new reasons to like him, they’ve found new ways to look at his achievement. Literary scholar Richard Halpern has suggested that Rockwell’s vision of America is aware of its own gaps, making his paintings “not so much innocent as . . . about the way we manufacture innocence.” The eminent art historian Alan Wallach has dared to see Rockwell’s “capitalist realism” as deeply ideological, along the lines of socialist realism.

Most reactions to Rockwell, however, continue to be decidedly simpler. Steven Spielberg has said, “I look back at these paintings as America the way it could have been, the way someday it may again be.” He and others have bought Rockwell’s bill of goods. But what these speakers, and these pictures, fail to grasp is that the special, courageous greatness of the nation lies in its definitive refusal of any single “American way.”

America isn’t about Rockwell’s one-note image of it — or anyone else’s. This country is about a game-changing guarantee that equal room will be made for Latino socialists, disgruntled lesbian spinsters, foul-mouthed Jewish comics and even, dare I say it, for metrosexual half-Canadian art critics with a fondness for offal, spinets and kilts.

I don’t want to live by the clichés of a wan, Rockwellian America, and I don’t admire pictures that suggest that all of us should. But I see why we need to look into how, in a world full of threats, so many of us have been soothed by their vision.

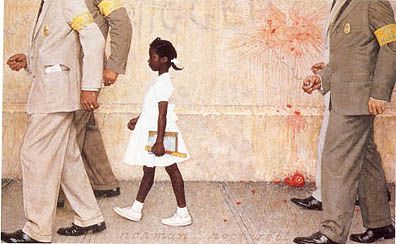

Obviously this elitist twit has not seen this:

The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell for Look Magazine

Or this:

Painting intended as the final illustration for Look story, “Southern Justice” by Charles Morgan, Jr., June 29, 1965. Unpublished, Oil on canvas. Norman Rockwell Museum Collection)

Now, can someone tell me just what the hell was wrong with Norman Rockwell?

Thanks– I’ve seen those Rockwell images, and they are great. Of course, Gopnik’s objection to Rockwell had nothing to do with courage– it’s merely the fact that Rockwell celebrated and honored the essence of America. For bien-pensant sheep like Gopnik, that’s not only wicked, it’s a sin against good taste.

Culturally and politically, this country has been overrun by a pack of villains from an Ayn Rand novel. Gopnnik is just another Ellsworth Toohey.

Can’t say that I disagree with that.

Well said David.